His accusers made it clear at the trial that Jan Hus would not only die, but that he would die without hope. “We take from you the cup of redemption,” the prosecutors solemnly intoned before sentencing. But Hus replied, “I trust in the Lord God Almighty… that He will not take away from me the cup of His redemption, but I firmly hope to drink from it today in His kingdom.”

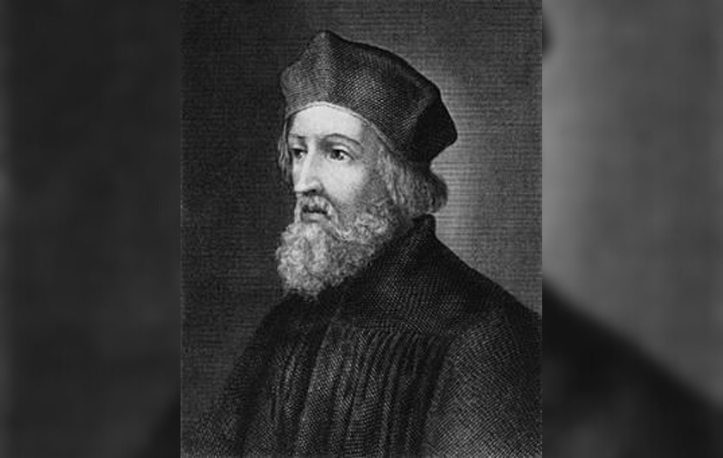

The communion cup was key to Hus’s crimes. Born in 1362 in the village of Husenic in southern Bohemia (today the Czech Republic), this son of peasants learned to pray at the feet of his mother. It was she who prompted young Jan toward the priesthood, where he might find, among other benefits, the money and prestige to escape his family’s poverty. An average but hard-working student, Hus received a master’s degree in theology from the university in Prague and became a preacher in that city’s Bethlehem Chapel in 1402. Shortly before, news had arrived from England of a certain John Wycliffe, a reformer, whose ideas soon split the university faculty. Chief among those ideas was the nature of the communion cup. Was the wine of the Lord’s Supper really changed into Christ’s blood during the Mass? Yes, argued the German and Roman theologians. No, countered many Czechs and Wycliffe supporters. Thus, the cup would become a symbol of reform that Hus, by some accounts, would carry to his pyre.

Times were dangerous in the early fifteenth century. The church was split between two popes, one in France, the other in Rome. The so-called Great Schism (1378-1417) meant that every leader, politician or churchman must take sides and hope his pope emerged the winner. Survival and the future of the church hung in the balance.

Meanwhile, Wycliffe’s influence on the preacher Hus was becoming a clear and present danger. In 1405, Hus began to speak against the sins of the clergy and denounce their hoaxes perpetrated on common parishioners. When the Bohemian church claimed that Christ’s blood was appearing on communion wafers, Hus exposed the scheme in language sure to make its point: “These priests deserve hanging in hell” for they are “fornicators”, “parasites”, “money misers”, and “fat swine”. Strong words in a volatile church climate. “They [priests] are gluttons whose stomachs are overfilled until their double chins hang down.” Later came Hus’s outrage against indulgences, the selling of heavenly favour used to finance papal wars. “Shall I keep silent?” he asked. “God forbid.”

Four times Hus was excommunicated. For two years (1412-14), he went into exile working in villages in southern Bohemia, writing, preaching, and keeping his head down.

Then, in October 1414, Pope John XXIII convened the Council of Constance and invited Jan Hus to attend. Two grand purposes filled the Council’s agenda: End the schism and eradicate heresy from Europe. Promised safe conduct, Hus accepted the invitation, joking that “the goose [hus in Czech means “goose”] is not yet cooked and is not afraid of being cooked.”

Within a week, he was arrested. For several months, Hus wasted away in a cell in the Dominican monastery on an island in Lake Constance, saved from death there only to face accusations that surely foretold a bitter death to come.

Hus’s critics brought the common charges: dangerous heretic, unworthy of the name Christian, wicked man, teacher of a fourth person in the Godhead—all charges to which Hus was forbidden to reply.

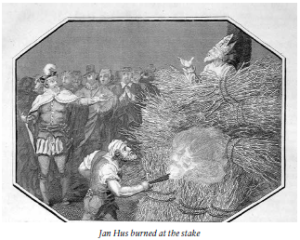

On 6 July 1415, amid shouts and jeers, the church committed his soul to the devil. Hus was pushed by a crowd through the streets of Constance to the piled tinder, wrapped by the neck to a stake, and set ablaze. He died singing, “Jesus, Son of the living God, have mercy on me.”

Submit a Prayer